Understanding Karāmah (spiritual wonder) vs Muʿjizah (miracle) in Islam

In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful

In Shia Islamic theology, a clear distinction is made between muʿjizah (miracle) and karāmah (spiritual wonder). While both involve extraordinary acts beyond normal human ability, they differ in purpose, context, and attribution. This article briefly explores and compares these concepts — alongside siḥr (magic) and draws upon classical Islamic theology and Persian-language sources, with references cited throughout.

Glossary:

- Karāmah = Singular: A single spiritual wonder or extraordinary act granted by Allah to a righteous person (e.g., a saint or mystic).

- Karamāt = Plural: Multiple acts of karāmah or a collection of wonders performed by saints or awliyāʾ.

What is a Muʿjizah (مُعْجِزَة)?

A muʿjizah is an extraordinary act (miracle) granted to a prophet by God as a proof of prophethood. It is usually accompanied by a challenge (taḥaddī) to others to replicate it, affirming the divine source of the message [1]. When commanded by God, prophets are obligated to demonstrate such miracles to establish the truth of their mission.

These miracles are exclusive to prophets. For instance, the Qur’an itself is considered the everlasting muʿjizah of Prophet Muhammad. Other examples include:

- Prophet Musa (Moses): His staff turning into a serpent, mentioned in multiple Qur’anic verses (7:107, 20:20, 26:32, 27:10, and 28:31).

- Prophet ʿĪsā (Jesus): Speaking as an infant, healing the blind and lepers, raising the dead, and forming birds from clay by God’s permission.

Although some Imams or saints may perform acts that appear miraculous, these are not muʿjizāt because they are not connected to a prophetic claim — such acts are classified as karāmāt (spiritual wonders) [2]. It is essential to emphasize that muʿjizāt do not arise from personal power. They occur solely by the will of God, with prophets acting as honored vessels of divine command.

What is a Karāmah (كَرَامَة)?

A karāmah is a supernatural act granted by God to a person who does not claim prophethood, such as the Imams or the awliyāʾ Allah (God’s close friends or saints) [2–4]. Unlike a prophetic miracle (muʿjizah), a karāmah is not accompanied by a challenge (taḥaddī) and is not intended to prove a divine message. According to Allamah Tabatabaei, karāmah is the result of a purified soul and deep spiritual closeness to God — it is not meant to serve as public proof of religious authority [5]. Rather, karāmāt are subtle signs of a person’s nearness to the Divine, often arising through their inner sincerity, moral refinement, and devotion.

Examples of Karāmah: What Can Righteous Individuals Perform by God’s Will?

These include ruyāhā-ye sādiqah (truthful dreams), which come true or accurately reflect reality; kashf, the unveiling of hidden matters; walking on water; ṭayy al-arḍ, or traversing vast distances instantly; and ishrāf bar ḍamāʾir, the ability to perceive the inner thoughts or states of others [6].

Understanding Magic and Illusion in Islamic Thought

Magic, in contrast to both muʿjizah and karāmah, is typically rooted in illusion, distraction, or rare natural tricks, and is often used for manipulation rather than spiritual elevation [7]. Unlike divinely granted wonders, magic can be taught and learned, and is frequently based on sleight of hand, psychological misdirection, and imaginative deception. Even when it has a natural basis, it is generally employed for harmful or misleading purposes, and is often entwined with superstition, ignorance, and false claims [8].

Qur’anic and Hadith Evidence for Karāmāt

According to Surah al-Naml (27:38), Prophet Sulaymān (AS) requested that the throne of the Queen of Sheba be brought to him. While the Qur’an does not specify who fulfilled this request, most exegetes identify the individual as Āṣif ibn Barkhiyā — a righteous man with knowledge of the Book [9]. Some, however, interpret the verse as referring to Prophet Sulaymān (AS) himself, while others suggest it may have been Prophet Khidr (AS) [10].

Another well-known example of karāmah is found in a narration from Abū Baṣīr, who asked Imam al-Bāqir (AS) whether the Imams could raise the dead or heal the blind. The Imam replied, “By God’s permission, yes,” and then passed his hand over Abū Baṣīr’s eyes — who was blind — and he was instantly able to see [11, 12].

Summary Table: Comparing Muʿjizah, Karāmah, and Magic

| Feature | Muʿjizah (Miracle) | Karāmah (Wonder of a Saint) | Magic / Illusion |

| Performed by | Prophet | Imam or Wali (saint, mystic) | Sorcerer, magician, or ascetic (i.e., Hindu or yogic ascetic) |

Purpose | To prove prophethood | Gift from God, sign of spiritual nearness | Impress, deceive, or manipulate |

Accompanied by challenge (tahaddī)? | Yes | No | No |

Must be shown publicly? | Yes, when commanded | No, often hidden or unintended | Often intended to attract attention |

| Requires divine permission? | Yes | Yes | No — relies on tricks or unknown forces |

Can it be taught or learned? | No | No | Yes — taught through training, rituals, or deception |

| Linked to a claim of prophethood? | Yes | No | No |

Key concluding remarks;

When we witness or hear about a spiritual wonder (karāmah) from an ʿārif, it may sound strange or even unbelievable — yet within the framework of Islamic theology, such occurrences are entirely possible. However, not every supernatural act qualifies as a karāmah. Only those performed by righteous individuals, with sincere intention and by divine permission, meet this standard. These wonders are not displays of personal power, but manifestations of wilāyah takwīniyyah — a form of cosmic authority granted by God. They are subtle signs of divine proximity, not public performances or prophetic claims, which is why such stories are often only shared after the demise of the ʿurafāʾ.

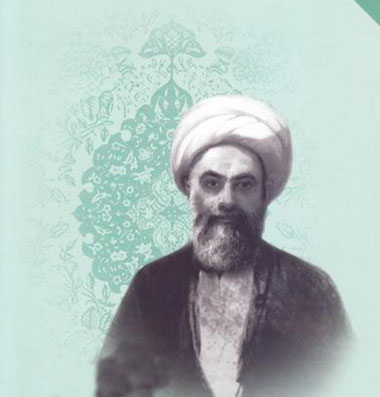

Still, it must be clearly emphasised: karāmah is not the goal of the spiritual path, nor should it be sought by the sālik (wayfarer). Muḥammad ibn Munawwar mentions about Shaykh Abū Saʿīd Abū al-Khayr [13]:

“They told the Shaykh [Abū Saʿīd Abū al-Khayr], ‘So-and-so walks on water.’ He replied, ‘A duck can do that.’ They said, ‘So-and-so flies in the air.’ He said, ‘So does a fly.’ They said, ‘So-and-so travels between cities in a moment.’ He replied, ‘Shayṭān crosses from East to West in a single breath.’ These things are of little worth. The true man is the one who lives among people — sits, walks, sleeps, trades, and interacts — and yet never becomes heedless of God, not even for a moment.”

This, ultimately, is the essence of true wilāyah: not outward feats, but inward constancy — the ability to remain with God, even amidst the noise and distraction of the world.

References:

- Qadrdān Qaramalkī, Miracle in the Realm of Reason and Religion, 1381 SH, p. 76.

- Misbāḥ Yazdī, Rāh wa Rāhnamā-shenāsī (Path and Guide Recognition), 1397 SH, p. 178; Jurjānī, al-Taʿrīfāt; Nāṣir Khusraw, p. 79.

- Jurjānī, al-Taʿrīfāt; Nāṣir Khusraw, p. 79; Sajādī, Farhang-e Maʿārif-e Islāmī (Encyclopedia of Islamic Concepts), 1363 SH, vol. 4, p. 15.

- Misbāḥ Yazdī, Āmūzish-e ʿAqāʾid (Teaching of Beliefs), 1384 SH, p. 221.

- ʿAllāmah Ṭabāṭabāʾī, Iʿjāz-e Qurʾān (The Miracle of the Qur’an), 1362 SH, p. 116.

- Sayyid ʿArab, “Karāmat,” p. 607.

- Misbāḥ Yazdī, Rāh wa Rāhnamā-shenāsī, 1397 SH, p. 179.

- Sayyid ʿArab, “Karāmat,” p. 609.

- Fakhr Rāzī, Mafātīḥ al-Ghayb, 1420 AH, vol. 24, p. 557.

- Quoted in Faḍlullāh, Min Waḥy al-Qurʾān, 1419 AH, vol. 17, p. 207.

- Al-Kulaynī, al-Kāfī, 1429 AH, vol. 2, pp. 523–524, hadith no. 3;

- Ṣaffār, Baṣāʾir al-Darajāt, 1404 AH, p. 262, hadith no. 1.

- Muḥammad ibn Munawwar, Asrār al-Tawḥīd, Book II – On the Middle Period of the Shaykh’s State, Chapter II – Sayings Narrated from the Shaykh, Story no. 16.

Leave a comment