From Shadows to Light: An Islamic Reflection on Plato’s Cave

In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful

Introduction

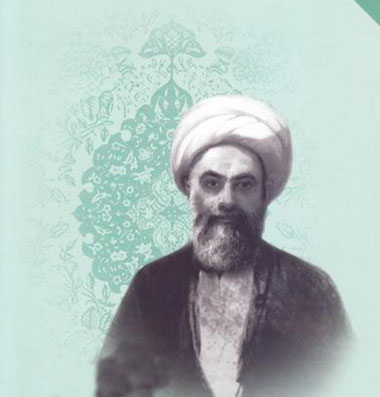

Plato (428/427–348/347 BCE), Arabised as Al-Aflāṭūn, is widely regarded as one of the most influential philosophers in history. A student of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle, his thought laid the foundation for much of Western philosophy [1]. His legacy, however, extends into the Islamic world, where he was often seen not just as a philosopher but as a sage with divine insight. Influential Muslim thinkers such as Al-Fārābī and Suhrawardī engaged with his works, praising their depth and relevance [2,3]. Within Shi’a Islamic scholarship, particularly in the Hawza of Qom, scholars such as ʿAllāmah Ḥasanẓādeh Āmulī have even suggested that Plato may have been a prophet sent to the Greeks, based on the moral and metaphysical purity of his teachings [4].

One of Plato’s most enduring contributions, the Allegory of the Cave, presents a powerful image of the soul’s movement from illusion to truth. This concept deeply resonates with the Qur’anic vision of prophetic guidance, which seeks to lead people from ẓulumāt (darkness) to nūr (light) [5]. Muslim scholars and mystics have long drawn on this parallel, exploring the cave as a spiritual metaphor within the Islamic tradition [6]. This essay explores Plato’s Cave through an Islamic lens, examining its philosophical and mystical dimensions. It considers how Plato’s allegory mirrors the prophetic mission in Islam: awakening the soul, confronting illusion, and guiding the intellect and heart toward divine reality.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave explained

Before exploring the Islamic thematic analysis from this allegory, it is important to first understand the narrative of Plato’s Cave Allegory. In The Republic (514a–520a), Plato presents a metaphor for the human condition and the nature of truth. A group of prisoners is confined in a dark cave, chained so that they can only face a wall. Behind them burns a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners, various objects are carried by unseen figures. These objects cast moving shadows on the wall, and the prisoners, having known nothing else, believe these shadows to be the full extent of reality [7].

Eventually, one prisoner is freed and makes the difficult ascent out of the cave. At first blinded by the sunlight, he gradually comes to see the world as it truly is — skies, water, animals, and light. He realises that the reality outside the cave is far more authentic than the illusions he once accepted. Compelled by a sense of duty, he returns to the cave to share what he has discovered. However, the other prisoners reject him, mock his claims, and refuse to leave the shadows. Plato suggests that, if they had the chance, they would kill him. This allegory symbolises the soul’s journey from ignorance to awareness, and the danger faced by those who challenge the comfort of illusion [7].

Plato’s Cave and the Prophetic Mission: An Islamic Reflection

1. Cave as the Age of Ignorance (Jāhiliyyah)

In Plato’s allegory, the prisoners are chained and only see shadows cast upon a wall. These shadows represent illusions mistaken for reality. Similarly, in pre-Islamic Arabia, society was immersed in ghaflah (heedlessness), tribal pride, idolatry, and blind imitation. The Qur’an refers to this period as Jāhiliyyah (the age of ignorance). The term Jāhiliyyah appears four times in the Qur’an: in Surah Āl ʿImrān (3:154), al-Māʾidah (5:50), al-Aḥzāb (33:33), and al-Fatḥ (48:26). One of these verses asks pointedly: “Do they seek the judgment of Jāhiliyyah? But who is better than Allah in judgment for a people who are certain?” (Surah al-Māʾidah 5:50).

Jāhiliyyah was not merely a lack of knowledge, but a deeply ingrained attachment to falsehood. People followed their ancestors blindly, defended corrupt customs, and shaped their religion to fit what suited their desires. Daughters were buried alive, wealth and lineage were worshipped, and truth was ridiculed such as in surah al-Takwīr 81:8–9; “When the girl [who was] buried alive is asked for what sin she was killed”. Quran described such people in surah al-Aʿrāf 7:179; “They have hearts with which they do not understand, eyes with which they do not see, and ears with which they do not hear”

2. From Contemplation to Revelation

Before receiving revelation, the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) would retreat to Ghar Hirāʾ for deep contemplation. In that stillness, he rejected the falsehoods of what the bedouin of the times used to believe. Then came the first command: “Recite in the name of your Lord who created” (Surah al-ʿAlaq 96:1). He was instructed to begin his mission starting with those closest to him: “And warn your nearest relatives” (Surah al-Shuʿarāʾ 26:214). Unlike Plato’s prisoner who stumbles into light, the Prophet was divinely chosen, granted knowledge of the unseen, and sent as a mercy: “We did not send you except as a mercy to all the worlds” (Surah al-Anbiyāʾ 21:107).

3. The Shadows as False Beliefs

In Islamic teachings, the shadows represent distorted beliefs and inherited systems that veil people from truth. These include idol worship, blind cultural imitation, and desires masked as principles. These verses include: “Shall we forsake our gods for a mad poet?” (Surah al-Ṣāffāt 37:36); “Even though their forefathers understood nothing, nor were they guided?” (Surah al-Baqarah 2:170); “Do they not look into the dominion of the heavens and the earth?” (Surah al-Aʿrāf 7:185).

The Qur’an links disbelief not just to ignorance but to a refusal to use the intellect: “The example of those who disbelieve is like one who shouts at a flock of sheep that hears nothing but calls and cries. They are deaf, dumb, and blind, so they do not understand” (Surah al-Baqarah 2:171). True faith must also penetrate the heart: “The Bedouins say, ‘We have believed.’ Say: ‘You have not [yet] believed; but say instead, ‘We have submitted,’ for faith has not yet entered your hearts” (Surah al-Ḥujurāt 49:14).

Islam identifies two forms of guidance: the external message of the Prophet and the internal guide of the intellect. Imam al-Ṣādiq (peace be upon him) explained: “O Hishām, Allah has placed two kinds of authority over man: the apparent and manifest authority, and the internal and hidden authority. The prophets and messengers are the apparent and manifest authorities, and the intellect is the hidden and internal authority” [8]. Revelation and intellect are meant to work together. One awakens the world, the other awakens the soul.

4. The Return: Daʿwah and the Challenge of Truth

Like the freed prisoner who returns to the cave, the Prophet returned to his people with divine truth. His message was not speculation, but revelation: “He does not speak from [his own] desire. It is nothing but revelation sent down” (Surah al-Najm 53:3–4). Many resisted him, clinging to inherited practices: “Indeed, we found our forefathers upon a religion, and we are following in their footsteps” (Surah al-Zukhruf 43:22). The Prophet’s mission was not merely to inform but to transform, calling humanity from darkness to light, from illusion to truth.

The Modern Cave: Distraction, Heedlessness, and the Path Inward

We are still in the cave. Today, it is not carved from stone but built from distraction, indulgence, and heedlessness. Its walls are reinforced by social media, entertainment, wealth, vanity, and the constant chase for comfort. The shadows we follow are not idols of stone, but illusions shaped by trends, screens, curated lifestyles, and ideas that suit our desires. We speak of Islam while bending it to fit our habits. We talk about the Hereafter while living as though it will never come. We claim belief in Allah, yet our lives reveal distance from Him.

“Has the time not come for hearts to humble themselves to the remembrance of Allah and what has come down of the truth?” (Surah al-Ḥadīd 57:16). We know the truth, but build our lives around illusion. Islam was not revealed to revolve around us. It was meant to transform us from within and guide us toward what is heavenly. Its purpose is not to affirm our desires but to purify them. We must ask: Is my income ḥalāl? Are my family decisions grounded in divine guidance? Is my prayer truly present or just performed? If our lives are shaped by the world and only dressed in religion, then we are still in the cave.

Yet Allah’s mercy remains. He sends light through the wisdom of scholars, the sincerity of the faithful, and the Qur’an itself. The question is not whether the light exists. It is whether we are willing to receive it. “They have hearts with which they do not understand” (Surah al-Aʿrāf 7:179).

Remaining in the cave is no longer about chains or shadows. It is about whether we choose to remain heedless or begin the inward work of transformation. Before revelation descended, the Prophet withdrew to Ghar Ḥirāʾ not to escape the world, but to prepare for truth. In that stillness, he received the command: Iqraʾ. In the same way, the seeker must turn inward, not to reject responsibility, but to gain clarity and strength. The true struggle is not outward. It is within. It is the battle against the beasts that grow within our spiritual heart such as pride, show-off, ego, laziness, corruption and the pull of worldly distractions.

This journey does not begin with extremes or sudden change. It begins with honesty, small steps, and consistent effort. True transformation unfolds through quiet reflection, stillness, and sincere intention. As we begin to look inward, we gradually release what clouds the heart, habits, attachments, and distractions that pull us away from clarity. The goal is not to abandon the world, but to remain within it while rooted in balance, presence, and submission.

Imam ʿAlī said, “Whoever knows himself has known his Lord” [9, 10). This saying is not merely a philosophical idea. It points to a path that begins with recognising the reality of the self, its limits, its needs, its contradictions, and ends with recognising the presence and majesty of Allah. It calls us to observe the self in the past, present, and future. When we understand our nature, our intentions, and our weaknesses, we begin to realise how dependent we are on divine mercy. Through that awareness, we come to know Allah.

This kind of self-knowledge is not just awareness of traits or emotions. It is the unveiling of the inner world, the confronting of the ego, and the humbling of the soul. The real veil is not the dunya itself but how we relate to it. When the seeker turns inward with sincerity, the soul begins to awaken. In that silence, we begin to hear the remembrance of Allah. In that stillness, we start to see with the heart. And in that return to the self, the heart begins to return to its Lord, not just through thought, but through transformation.

Stepping Out of the Cave

Plato’s cave is more than an ancient allegory. It is a mirror that reflects not only the ignorance of past societies but also the illusions we continue to embrace today. The Qur’an, the prophets, and the awliyāʾ have always come to unchain the soul from false attachments and call us to the clarity of divine truth. Yet, just like the prisoners who rejected the one who returned with light, people continue to resist voices that challenge their comfort and constructed realities.

The prophetic mission is not simply to inform. It is to awaken. It urges us to rise above inherited assumptions, superficial attachments, and lives shaped by shadows. This awakening often comes with difficulty. It may cost us our comfort, our approval, or our ease. But the path remains open.The journey from illusion to truth begins with sincerity. It requires the courage to confront the self, to ask what we fear, and to leave behind what is familiar but false. The cave is not only a symbol. It is a choice. It can remain a prison, or it can become a place of transformation.

If we are honest in our search, if we walk with both revelation and reason, and if we purify the heart alongside the intellect, then we may taste what the prophets lived and what the ʿurafāʾ pointed toward. Not just knowledge, but insight. Not just sight, but seeing with the heart. And in that vision, the soul begins to taste maʿrifah, the intimate recognition of its Lord.

References:

- Meinwald CC. Plato. Encyclopaedia Britannica [Internet]. 2025 Apr 22 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Plato

- Al-Fārābī. On the Perfect State. 1996.

- Suhrawardī SD. The Philosophy of Illumination. 1999.

- Ḥasanẓādeh Āmulī H. Qurān, Burhān, wa ʿIrfān az Ham Judāyī Nadārand. 1991.

- The Qur’an. Surah al-Baqarah 2:257.

- Shadi H. Escaping Plato’s Cave as a Mystical Experience: A Survey in Sufi Literature. Religions. 2022;13(10):970. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100970

- Plato. The Republic. Translated by Bloom A. New York: Basic Books; 1968. Book VII, 514a–520a.

- Al-Kulaynī M. Al-Kāfī. Vol. 1, hadith 13. Tehran: Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmiyyah; n.d.

- Al-ʿAmulī R. Mīzān al-Ḥikmah. Hadith no. 12223.

- Al-Turayḥī F. Ṣafīnat al-Biḥār. Vol. 2, p. 603.

Leave a comment